The Rage-Bait Republic

A few weeks ago, American Eagle ran a denim ad with Sydney Sweeney, in which she chirpily announced, “My jeans are blue.” Within hours, it seemed, vast corners of the internet had decided it was a secret handshake for eugenics, a fashion ad as fascist manifesto. The White House weighed in, a senator issued a statement, and a week later, nobody could quite recall what the original sin had been, only that they had once again been righteously furious. This is not how a serious society behaves; it is how a primed audience reacts to a genre that has quietly become the dominant form of political communication online: ragebait.

The contemporary right has understood this better than anyone. It has taken a cluster of genuinely complex issues—gender, trans rights, pronouns, diversity policies—and turned them into a travelling freak show, forever pointing at the most fringe Tiktok or the daftest campus leaflet and saying: look, this is what the left really believes. The trick is simple. You do not engage with what your opponents are actually arguing; you curate their worst, weirdest and least representative outliers, then replay them on a loop until they stand in for the whole. The result is an ecosystem in which conservative media talks about neo-pronoun discourse, bathrooms, and drag story hour far more than any left-wing party or NGO ever does, and then accuses the left of being obsessed. They are not describing a madness that already exists; they are manufacturing it, and inviting the rest of us to mistake the funhouse mirror for a portrait.

Analyses of the backlash against American Eagle show that although some progressive writers criticised the campaign, the idea of a large left-wing backlash was mostly created by conservatives, who amplified a few critical posts to craft and widely spread a story of liberal hysteria.

Sadly, technology is the steroid for this. Ragebait is what you get when people discover that anger is cheaper than imagination. The business model is simple enough that even a venture capitalist could understand it: platforms are paid in attention, anger is the most reliable stimulant, so the supply of manufactured outrage expands to meet demand. The algorithm doesn't concern itself with your feelings; it only cares that you have feelings.

The damage is not just that it wastes time; it corrodes moral attention. After enough of it, people stop asking “Is this true?” and start asking “Which side am I supposed to hate?” Public discourse turns into a permanent dress rehearsal for the mob. Every day offers a new heretic to burn, a new screen onto which we can project our grievances. If the novelist’s job is to complicate our sense of other people; ragebait’s job is to flatten it.

There are, fortunately, ways to refuse conscription into this little war. The first is to treat your own anger as a warning light, not a mandate. When a post spikes your pulse, pause long enough to ask the oldest, dullest questions in the world: who says, about whom, on what evidence, and what might be missing? Very often the thing that enrages you most is precisely the thing that has been left out. Starving ragebait of what it needs—your clicks, your comments, your quote–tweets—may feel paltry, but every addiction is starved the same way.

A better internet would not be one in which no one is ever angry; it would be one in which anger has to pass through the customs of evidence and context before it is allowed in. The kind of content worth rewarding is slower, more specific, and frankly more demanding: essays that admit what they don’t know, reporting that names its sources, arguments that concede where the other side might have a point. It will never compete with outrage for sheer, adrenalised thrill. But it has one large advantage over ragebait: when you close the tab, you are a little clearer, not a little cheaper.

There is, after all, hope, and it looks refreshingly like politics rather than performance. In New York, Zohran Mamdani just won power the unfashionable way: by talking, relentlessly, about rent, wages, transport and landlords instead of whatever today’s culture‑war clip was demanding he react to. In Germany, Heidi Reichinnek has carved out similarly improbable results by refusing to audition for the part of internet lunatic and hammering away at a short list of material questions—housing, jobs, basic security—that actually structure people’s lives. They are proof that you do not have to dance to the algorithm’s tune; you can tune it out and still win, if you insist on treating voters as tenants, workers and citizens rather than as eyeballs to be goaded into perpetual rage.

Here are a few things I’ve been reading lately — not all of which I’d sign my name to, but each provocative enough to merit the time it takes to disagree with them.

nuff said.

•

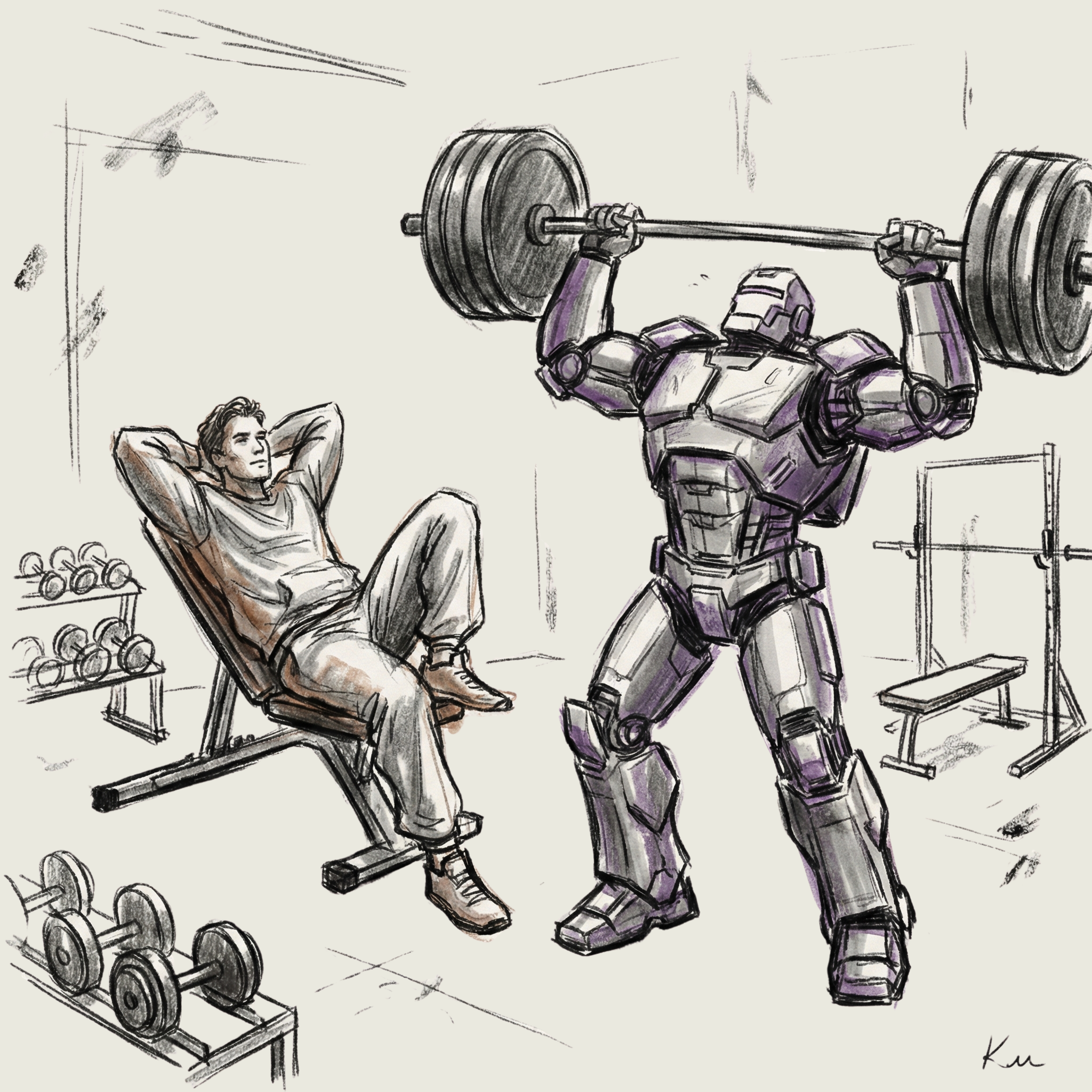

We should all think very carefully about where to get help from AI. Daniel Miessler offers a useful Job vs. Gym analogy to help determine when it is and isn't appropriate.

•

Here's a text that examines the history of the universe that led to your existence and reduces the pressure to be exceptional by highlighting your small place in the cosmos. It invites us to let go of the chase for grand significance and instead find meaning in everyday moments, relationships, and work. I liked it.

You've reached the end. Just out of curiosity: if you've read this far, please reply to this email. You don't have to write anything in your response.