Dehumanisation as a Service

We have reached a peculiar moment in technological "progress" where we can purchase convenience on the explicit condition that we remain willfully blind to its mechanics. Before we get into it: Have you heard of NEO, the humanoid robot you can now buy?

The marketing promise is cleanly seductive: NEO will vacuum our floors, fold our laundry, take out our trash, and engage us in conversation. It will do this, we are assured, through artificial intelligence—through machine learning, computer vision, and autonomous decision-making. The robot, in other words, will be ours in the truest sense: a possession that labours without complaint, without rights, without the inconvenient reality of human need. Let's assume for a moment that this is more than just a promise or a marketing gimmick (They've taken a page from Elon Musk's playbook: you can give the company $20,000 already, but the product doesn't really exist yet).

The deception lies not in what NEO can do but what marketing insists NEO is. Because when the system cannot accomplish a task, which is every task so far, a human worker remotely takes over. They see through NEO's cameras; they manipulate NEO's arms; they make the decisions NEO cannot. All the while, the interface is designed so that you, the customer, will never see this person. You will never observe their face. You will never catch a glimpse of their features or acknowledge their presence. They are deliberately erased from the transaction, replaced by the comforting fiction of autonomous machinery. This is not automation. This is outsourcing with an exceptionally cruel user interface.

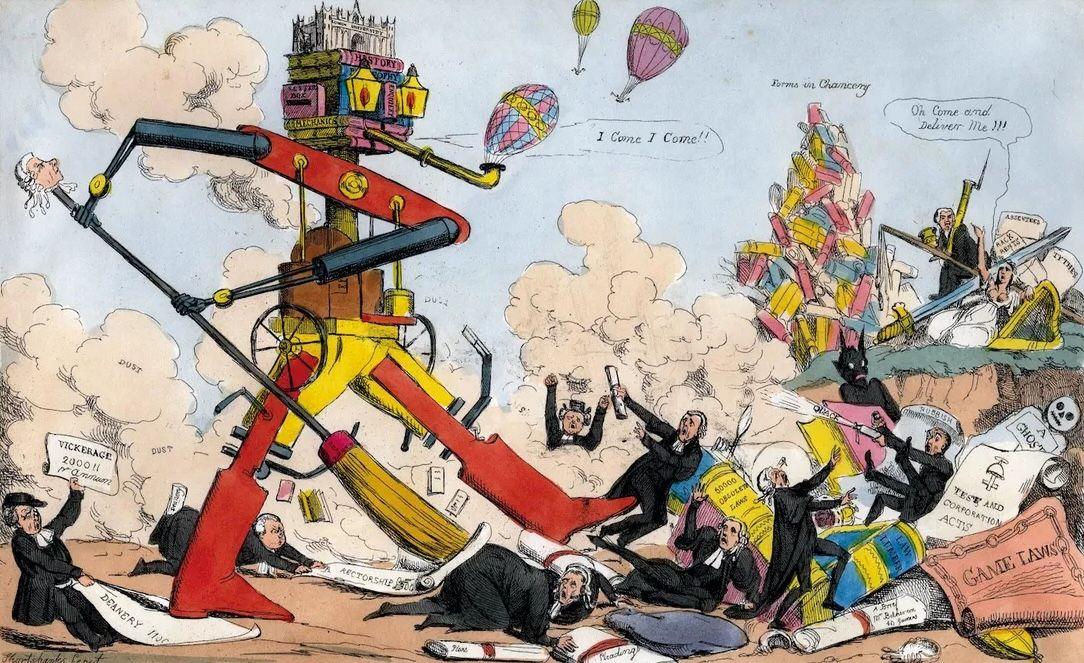

The architects of this system are counting on an ancient human weakness: the willingness to accept comfortable falsehoods when confronted with them repeatedly. We've seen this before, not just in our present world, but in the dystopian nightmares of literature, where writers dare to imagine what happens when we systematise the denial of human dignity.

Consider Philip K. Dick's Ubik, in which artificial humans called "pneumatic" beings perform labour indistinguishable from that of their creators. The horror of Dick's vision isn't merely that these beings exist but that no one can quite decide whether acknowledging their suffering matters. The boundary between tool and person becomes deliberately obscured, and society proceeds as though the obscurity were a feature rather than a confession.

In Aldous Huxley’s "Brave New World," individuality is sacrificed for comfort, pleasure, and efficiency. Humans are manufactured in hatcheries, conditioned and sorted into castes—each group engineered to be content with its allotted station, however menial. The very notion of personhood is eroded not by force, but by the population’s voluntary surrender to convenience and distraction. This structural dehumanisation finds a fresh echo in the way NEO—a robot butler, its human labourers hidden—invites us to outsource not only work, but empathy. Huxley warned that the greatest danger lies not in overt repression, but in our willingness to accept a life so mediated by pleasure and efficiency that awareness of exploitation becomes unnecessary. Where Orwell feared the boot, Huxley feared the drug: social order kept stable not with pain, but with soma—an anaesthetic that makes truth both inaccessible and irrelevant.

Similarly, NEO’s design doesn’t just block faces; it offers us a kind of digital soma: the erasure of uncomfortable facts and the reduction of workers to the status of invisible functionaries. What Huxley foresaw—the triumph of engineered happiness over hard empathy—becomes a reality in every line of code designed to blur a human out of sight. In this, we see not only a system that denies dignity, but a society quietly content to trade it away for the ease of never having to notice.

The most unsettling comparison, however, belongs to the work of Margaret Atwood, whose Handmaid's Tale describes a society built on the systematic invisibility of certain people's humanity. The Handmaids are present but unobtrusive; their labour is essential, but their personhood is to be ignored. They perform necessary functions while their fundamental nature as human beings is legislated into irrelevance. One need not be a prophet to notice the resemblance: NEO's design actively legislates the worker into irrelevance. The app lets you block rooms and blur faces, as though the company were offering you a feature when, in fact, they are offering you moral distance—the technological equivalent of not having to see.

What makes this particularly egregious is the precise dishonesty involved. If 1X Technologies believed in their product as an autonomous machine, they would not employ remote workers. The remote workers are not a fallback position but the actual one. They are the system. The "artificial intelligence" is marketing copy for a sophisticated webcam attached to a puppet, puppeteered by humans whose working conditions, compensation, and dignity are deemed too embarrassing to mention. This is neither robotics nor artificial intelligence in any meaningful sense. At best, it is a novel form of manufacturing remote labour consent. At worst, it represents the industrialisation of dehumanisation.

Consider what is being sold: not a robot, but a relationship of concealment. You pay $20,000 or $499 monthly to purchase the right not to think about the person making your life easier. The company profits not from the efficiency they provide, but from the psychological comfort they enable—the comfort of convenience without conscience, labour without obligation, service without acknowledgement of the servant. It is rather brilliant in the way that most moral catastrophes eventually reveal themselves to be.

The critical question—neither the marketing materials nor the tech press seems inclined to ask—is this: if a system requires human intervention to function, why pretend otherwise? Why not simply employ a human directly? Why the elaborate theatre of robotics, the AI veneer, the carefully designed interface that obscures human presence? The answer, of course, is that the deception is the product. The customer buys not a functional service but psychological absolution. They purchase the ability to participate in a consumption system without confronting its human cost. They obtain the fiction of progress without the reality of exploitation—or rather, they obtain exploitation with aesthetics so superior that exploitation becomes invisible.

This distinguishes NEO from a mere business model: it is a business model married to a technology of forgetting. It's a robot butler. It uses AI to do your chores. It's fully automated, except it isn't. Sometimes it can't do your chores, so a person controls it. But don't worry—you don't have to see their face. You don't have to see their features. You don't have to view them as human, because it's a robot. A robot that does your chores with AI, except when there's a human behind these eyes. Then a human's doing your chores, but you don't have to acknowledge that. This argumentation is not incidental to NEO's design. It is NEO's design.

This is what moral bankruptcy looks like when dressed in the language of technological progress. It is what exploitation sounds like when described in press releases. It is what dehumanisation becomes when it's packaged as convenience.

The responsibility here extends beyond 1X Technologies, though they have certainly earned their share. It extends to every technology writer, venture capitalist, and consumer who examined this product and failed to ask the simple, obvious question: If a human is doing the work, why are they not acknowledged? Why is their labour disguised as machine operation? What are we trying to forget?

We seem to believe that applying a sufficient technological veneer to human suffering prevents it from being suffering. We imagine that if we hide the worker behind enough layers of interface design, they somehow become less human, less deserving of dignity, less deserving of acknowledgement, less deserving of basic honesty about what is occurring.

This is not the future. This is the past, with better marketing. NEO is not a humanoid robot. It is a machine designed to make us more comfortable with dehumanisation. It is a technology whose fundamental purpose is not to automate labour but to automate our refusal to see the labour being performed. And in that distinction lies the genuine horror: not that we have built robots, but that we have built a system so sophisticated at making us not see that we mistake invisibility for innovation.

The question now is whether we will continue to purchase this fiction, or whether we might finally insist on honesty. Given the current trajectory, I know which way the wager lies—but one always hopes to be wrong.

The Woman Who Predicted Tech Fascism

More than 25 years ago, journalist Paulina Borsook warned of a toxic, libertarian-tinged ideology emerging from Silicon Valley. In her 2000 book, Cyberselfish, she sharply criticised tech’s immature, selfish, and Ayn Rand-inspired culture. Here's a recent interview with her – I highly recommend watching it.

Here are a few things I’ve been reading lately — not all of which I’d sign my name to, but each provocative enough to merit the time it takes to disagree with them.

Sam Altman tries to push LLM's creative writing as touching. "This is not literature as 'entertainment,' no. It’s literature as propaganda," writes Rachele Dini. She examines OpenAI's claims about ChatGPT's creative writing skills, Big Tech's weaponisation of grief and nostalgia, and the collapse of the academic humanities.

•

Everything about this is horrifying. And if this doesn't enrage or scare you, you're protected by privilege.

•

"By resisting surveillance and extraction and pursuing goals such as affordability, dignity, and justice, New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani can show how technology can truly serve the people. The first step is to protect immigrants."

You've reached the end. Thank you for reading!